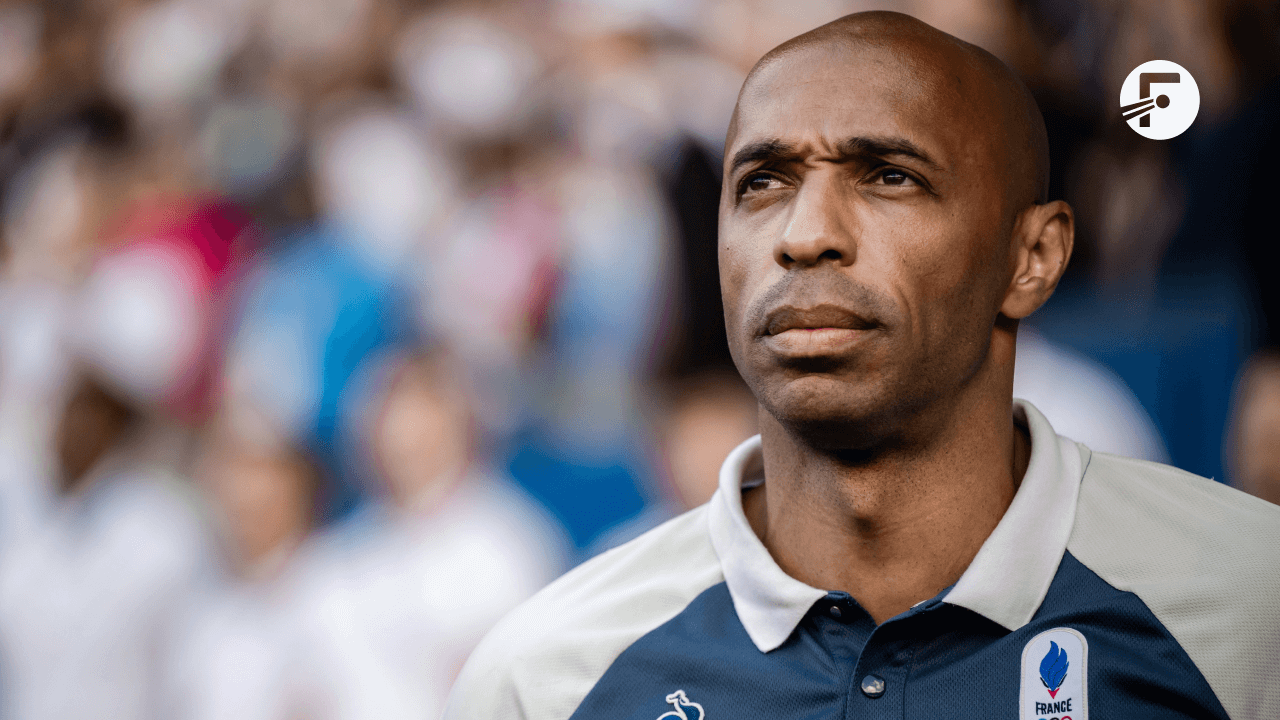

France were denied the fairytale ending to the men’s football tournament at the 2024 Summer Olympics as Spain defeated them in extra time in the final, but they had a successful tournament on the whole as they won their first Olympic medal in four decades. Surely, then, Thierry Henry’s first international tournament as a head coach must be considered a success.

By Neel Shelat

Given their recent success at the senior international level under Didier Deschamps, it might be quite surprising to learn that France failed to qualify for the men’s football tournament for five consecutive Olympics since the turn of the millennium. They did not fare too well in Tokyo 2020 either, getting knocked out of the group stage after losing to Mexico and getting hammered by the home team.

Now as the hosts themselves, they had a much better campaign in 2024. Les Bleus won their first medal in 40 years, meaning it was their first in the under-23 era of the Olympic tournament. Of course, having a mightily talented squad went a long way in helping achieve this success, but head coach Thierry Henry deserves his fair share of credit too.

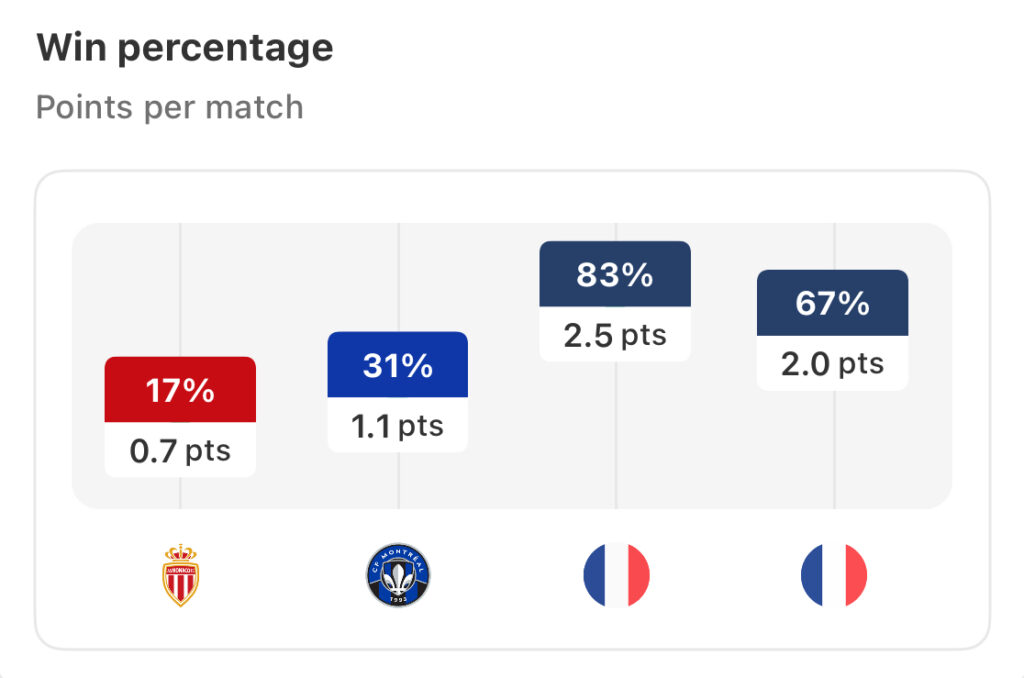

The legendary Arsenal striker’s previous track record as a head coach was pretty poor as he endured unsuccessful stints in charge of Monaco and CF Montréal. He now seems to have found the perfect job in international football, where he gets to work with some of the world’s most promising talents.

The 46-year-old Frenchman certainly enjoyed his best tournament as a coach at the 2024 Olympics, so let us take a look at how he fared from a tactical and analytical viewpoint.

A Player-Focused Approach

Unlike club football where the manager can have a lot of say about the kinds of players they want, international football leaves the coach’s hands fairly tied in terms of the personnel they have to work. Of course, they get to pick from the pool of eligible players, but the distribution of quality across the squad will ultimately be fairly random, particularly at youth levels.

The French under-23 national team head coach has always enjoyed a top-class talent pool to work with, so Henry certainly did not have to contend with a glaring lack of quality in any part of his squad. He did, however, have some tough decisions to make in terms of who he selected and who would get starting spots, while fitting all of his best players in a coherent XI was no straightforward task either.

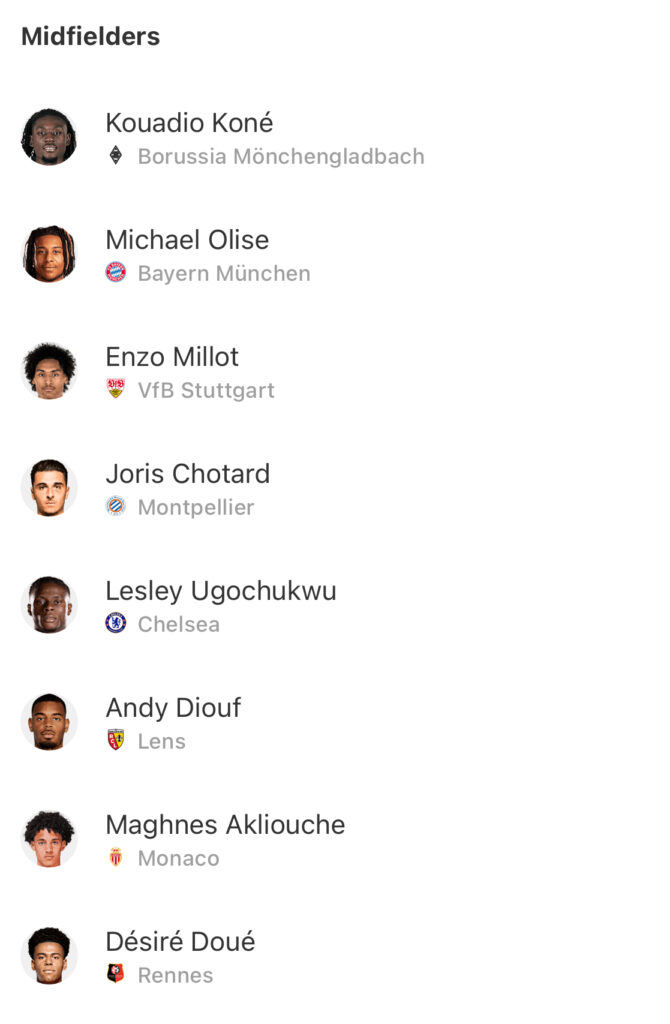

Consider the midfield department, where France called upon a diverse group of players plying their trade across Europe’s top leagues. Among them were established Borussia Mönchengladbach defensive midfielder Manu Koné, soon-to-be Bayern Munich star Michael Olise, Stuttgart talent Enzo Millot, Monaco starlet Magnes Akliouche and a man coveted by many of the world’s biggest clubs in Désiré Doué.

Of course, there was no way to field a sensible XI with all of these players, but even finding the best combination was a complicated process. Ultimately, Henry had to come up with an out-of-the-box solution.

Unique Tactical System

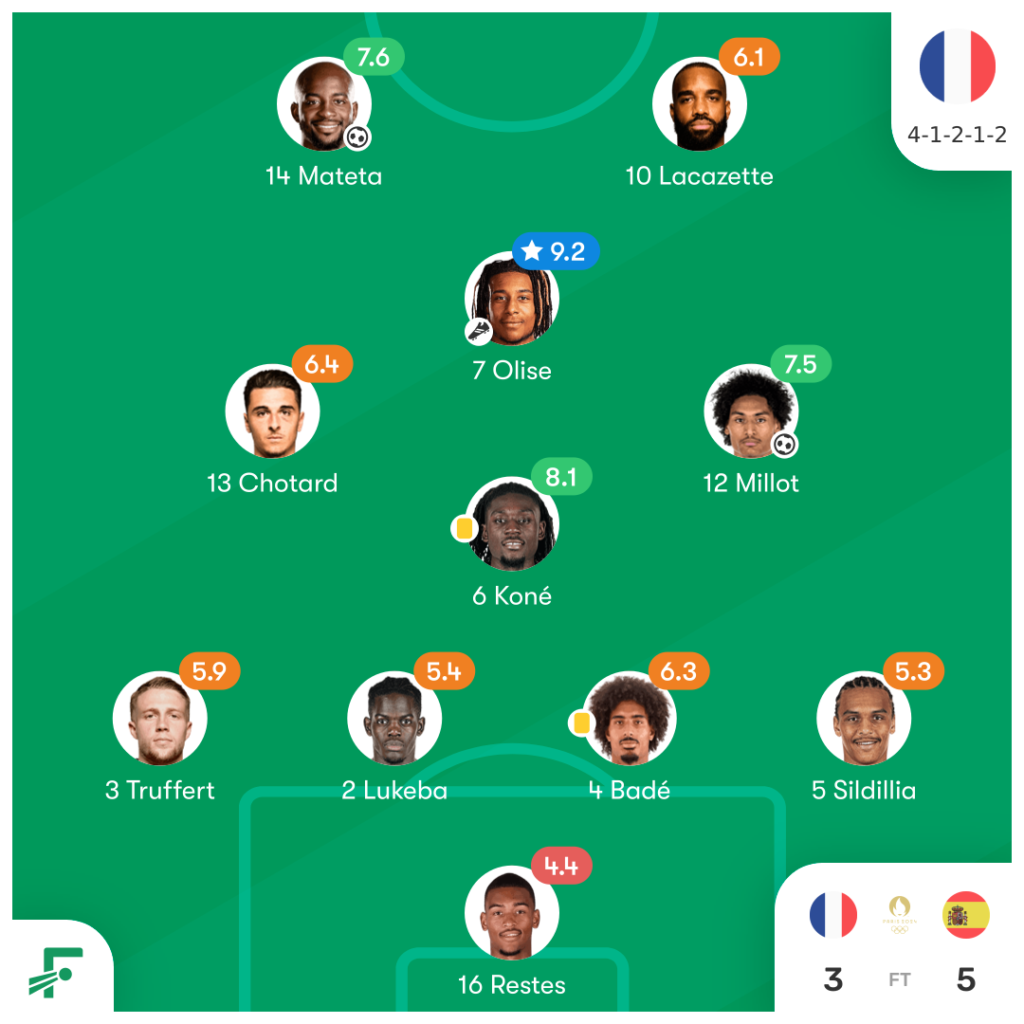

Considering the nature of his squad which included two star overage strikers in Alexandre Lacazette and Jean-Philippe Mateta besides this cohort of midfielders, Henry devised a rather unique 4-3-1-2 system.

He stuck to not just the formation but also a first-choice starting XI throughout the tournament, as the defensive unit remained unchanged in every meaningful match, Koné and Olise were fixed on either tip of midfield with Millot and Chotard partnering them for the most part, and the front two naturally picked itself.

This 4-3-1-2 system gave them a lot of attacking advantages which we will soon touch on, but the key to making it work was having a good out-of-possession plan. The lack of wingers or wide midfielders in this formation makes teams using it susceptible to being threatened down the flanks, but France prevented that from happening by setting up in a high block and setting pressing traps as they initially allowed teams to pass out wide to their full-backs before springing, with the ball-side midfielder pinning the full-back in using the touchline and the remaining trio tightly marking their counterparts to prevent any easy passing options.

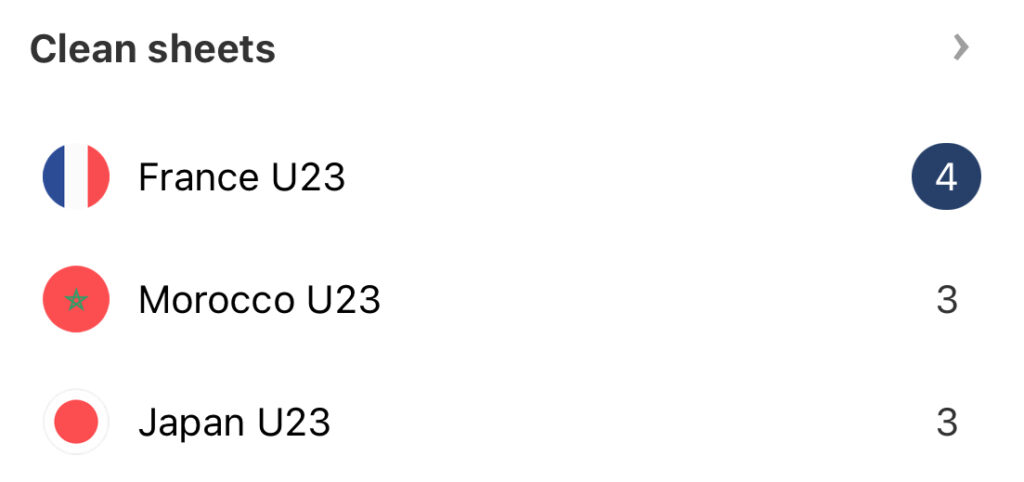

Using this approach, Les Bleus kept the most clean sheets in the tournament and conceded just one goal en route to the final.

Their attacking play was more eye-catching, though, largely thanks to Henry’s willingness to give his stars the freedom to deal damage in their own way. He platformed them with a back-three formed by asymmetric full-back movements, as Kiliann Sildillia stayed deep and used his centre-back-like passing qualities, while Adrien Truffert got forward freely on the left. Beyond them, Koné stuck to his task at the base of midfield and was supported by Chotard when needed, while Olise enjoyed full freedom in a number ten role from where he often drifted out to his favoured position on the right wing, while Millot hovered around him.

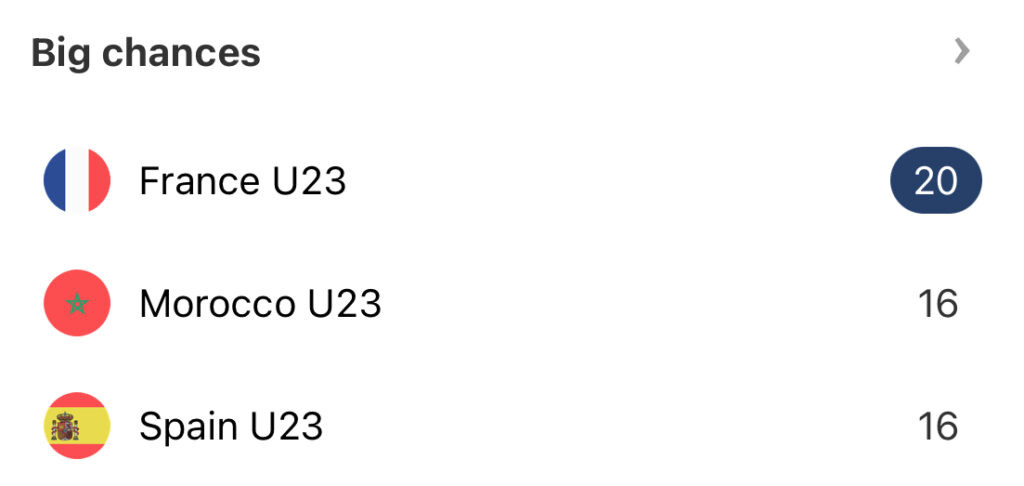

With that, as well as some clever in-match tweaks from Henry such as asking his strikers to swap positions in the final third if needed to ensure Mateta always attacked crosses at the back post against Egypt, France generated some of the best attacking creation of the tournament even though they often faced staunch low blocks.

Ultimately, Les Bleus were just about beaten on the big day by Spain, who have gotten quite used to winning across all levels of late. On the whole, though, they were right up there as one of the very best teams at the Olympics in terms of squad quality, tactical setup and execution, so all of their players and coaching staff should be quite proud of the job they did.

(Cover image from IMAGO)

You can follow Thierry Henry’s next move by using FotMob. Download the free app here.